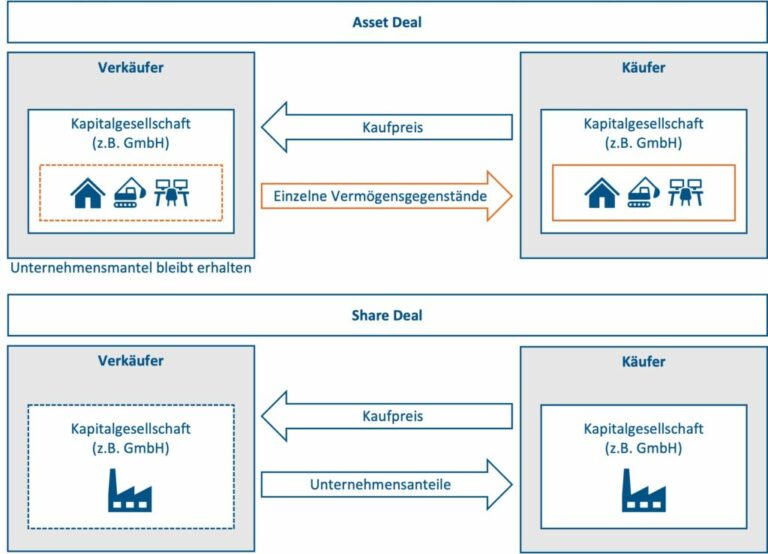

In a share deal, as the name suggests, shares are acquired, meaning the company is acquired as a whole – with all associated assets, rights, liabilities, and obligations. This is also referred to as universal succession.

In a share deal, the transaction does not affect the valuation of the acquired company’s assets; rather, their previous book values are carried forward.

In an asset deal, on the other hand, specific assets are acquired. The company’s rights remain the property of the seller. The buyer can therefore specifically select individual assets in an asset deal or, conversely, deliberately refrain from acquiring certain assets.

In an asset deal, the total purchase price of the acquired assets (including the assumed liabilities) is added to the individual acquired assets on the buyer’s balance sheet up to the amount of their respective market value. Thus, these assets generate greater tax depreciation potential for the buyer in the future and, if taxable income is generated, a corresponding tax savings. If the total purchase price (including assumed liabilities) exceeds the market value of all acquired assets, the excess amount is also capitalized on the purchaser’s balance sheet as goodwill and is subject to a tax depreciation period of generally 15 years.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Two Transaction Variants

Asset Deal More Complex

In an asset deal, unlike a share deal, the assets to be acquired must be listed individually and completely. This list can be very time-consuming when drafting the contract, as extensive appendices must be created listing all assets to be acquired. In practice, something is easily “forgotten.”

It is also of great importance in practice that in an asset deal, all contracting parties must sooner or later agree to the transfer of their contractual relationships to another legal entity. This consent is usually granted. Transitional solutions are possible. However, the process can be laborious and time-consuming.

In the case of public-law permits, certain licenses, and the like, a transfer to another legal entity is either impossible or disproportionately expensive. An asset deal is then usually ruled out as a structuring option.

In a share deal, the existing contracts remain unaffected. However, some contracts (usually the really important ones!) may contain “change of control” clauses. These are clauses that give the contracting party the right to terminate in the event of a change of shareholders. For example, almost all loan agreements contain such provisions.

In our experience, the contractual structure of a share deal is often only simpler at first glance. This is because the complete takeover of the entire company, including all rights and obligations, requires extensive negotiations elsewhere. Guarantees, warranties, and indemnities play a central role in contract negotiations in a share deal.

Asset deals can be tailored more individually and are sometimes unavoidable

For both the buyer and the seller, an asset deal offers the advantage of better controlling the scope of the transaction by acquiring only specific assets. This allows the buyer to exclude unwanted liabilities and assets from the acquisition. The reasons for this can be varied:

In the case of corporate units with a long and varied history, for example, a buyer may wish to use this method to protect themselves from past risks. When carving out and selling sub-activities from a company that are not legally separated (“carve-out”), an asset deal is often unavoidable.

Conversely, as already described, contracts whose transfer is explicitly desired (e.g., customer contracts, distribution agreements, etc.) can and must be transferred separately. If, for example, liabilities or continuing obligations are transferred to the buyer, the explicit consent of the respective creditor is required. In a share deal, however, the contractual relationships are transferred automatically by virtue of universal succession (with the exception of the aforementioned contracts with a “change of control” clause).

However, even in an asset deal, the scope for structuring the transaction is sometimes limited. This particularly applies to existing employment relationships. Indeed, even in an asset deal, employment relationships are transferred virtually “automatically” to the buyer. As a rule, the transaction will constitute a transfer of business pursuant to Section 613a of the German Civil Code (BGB). Whether a transfer of business has occurred should always be assessed individually by an employment lawyer in each individual case.

In addition to employment relationships, there are other obligations and liabilities in an asset deal that can be transferred to the purchaser by law, even without this being explicitly stipulated in the purchase agreement (e.g., tax debts or liability for the continuation of the business).

Corporate shell remains with the seller in an asset deal

For the seller, an asset deal results in the retention of the corporate shell (e.g., GmbH, KG, GmbH & Co KG) along with some assets, liabilities, and obligations.

These remaining positions are then the responsibility of the seller to settle after the transaction. This may raise very practical questions: Who can and wants to handle the settlement? Will access to premises, IT, files, and relevant employees be maintained? How should potential tax risks be addressed, which may be addressed by tax audits conducted after the transaction?

Tax Considerations[1]

If the company being sold is a corporation and the seller is also a corporation (e.g., GmbH, AG), only 5% of the capital gains are taxed in the share deal, which corresponds to a tax rate of approximately 1.5% (30% of 5%). This applies in any case to a minimum shareholding of 10%. If the capital gains are distributed to a natural person, the distribution is then subject to capital gains tax of 25% (plus solidarity surcharge and, if applicable, church tax). The total tax burden is then approximately 27.5%.

If the seller of shares in a corporation is a natural person, the so-called “partial income method” (60% of the profit at the respective personal income tax rate) applies to the share deal. In the case of the highest tax rate, this corresponds to a tax burden of approximately 28.5%.

In an asset deal, however, the profit of a corporation from the sale of individual assets is subject to taxation at approximately 30% (trade tax and corporate tax).

If the annual profit is distributed directly or indirectly to a natural person as a shareholder, the “withholding tax” of approximately 27% increases the tax burden to approximately 48.5%. This means that, in absolute terms, the asset deal initially appears significantly more negative for the seller.

However, even in an asset deal, the tax rate remains at only around 30% if the natural person as the seller retains all or part of the sales proceeds in the GmbH. In this case, the withholding tax is not payable on the retained amount. With a sufficiently high purchase price, a transfer to private assets is often undesirable, even regardless of the tax advantages.

One man’s loss is another man’s gain… because for the buyer, the advantage is usually the other way around!

For the buyer, an asset deal is more tax-attractive for profitable companies, as in this case, the acquired assets can be depreciated to reduce taxes under commercial and tax law.

In the case of a share deal, however, the acquired company shares are not subject to regular depreciation, so no tax advantage can be generated.

Value Increase Potential through an Asset Deal

Due to the divergent tax interests between the buyer and seller, the seller in an asset deal will want to participate in the buyer’s tax advantage. In any case, the seller will at least expect compensation for their tax disadvantages.

Especially if the company being sold generates stable profits and a large portion of the purchase price can be allocated to assets with short depreciation periods, the buyer realizes significant tax benefits with an asset deal. This advantage can easily amount to 20% to 30% of the purchase price for the buyer.

It becomes particularly interesting when this advantage does not correspond to an equally significant disadvantage for the seller. If this is the case, appropriate structuring can create real net added value for both parties.

Real estate is different

For transactions that are heavily influenced by real estate values, the property transfer tax can reach such a significant level that special transaction structures must be developed. The required consent from landlords to transfer leases can also make asset deals extremely difficult or even impossible (for example, in brick-and-mortar retail).

Exact calculation of the advantage is not always easy

We usually experience this in the case of the parties first negotiating a purchase price (cash and debt-free) as a share deal before the asset deal comes into play. Then, transparency regarding the after-tax financial impact of both transaction variants must be created. This is often not an easy task.

In an asset deal, not all contracts and liability risks are typically assumed by the buyer. Therefore, the seller should assess the opportunities and risks associated with the transaction as carefully as possible. The outcome is then crucial both for the decision regarding the transaction structure – asset or share deal – and for the determination of the purchase price.

Conclusion

Under certain conditions, an asset deal can create additional value for both buyer and seller. Tax advantages, risk considerations, or the need to legally separate previously dependent activities may be arguments in favor of an asset deal. However, the practical implementation of an asset deal can be complex because all contracts must be transferred.

Careful calculation and consideration of the advantages and disadvantages as early as possible in the transaction process are beneficial for making the right decision.

[1] Many thanks to the colleagues at dhmp https://www.dhmp.de/ for the input on the tax section