Multiplier Methods

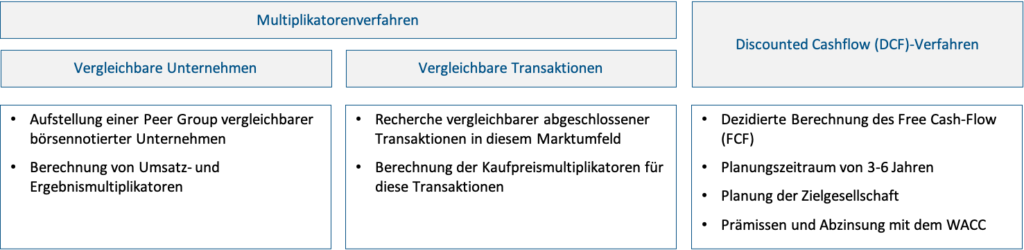

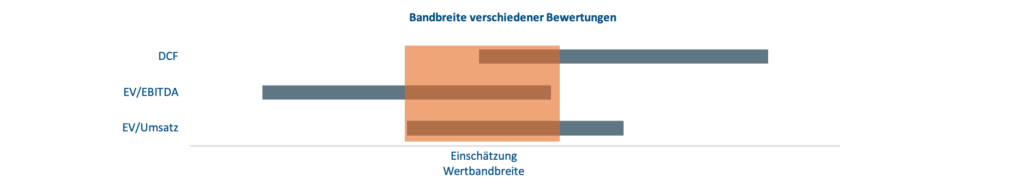

Multiplier methods are simple and quick methods for company valuation and are therefore frequently used in practice. The multipliers, often called multiples, are derived more or less systematically from a group of comparable companies. These can be comparable listed companies or transactions involving shares in comparable (non-listed) companies.

In practice, three multipliers are used:

- Sales multiplier – When companies are growing rapidly and/or no positive earnings figures are available

- EBITDA multiplier – For companies with cyclical investment behavior

- EBIT multiplier – For companies where investments occur regularly or play a minor role

In most cases, EBIT is used as the basis for valuing established companies, as EBIT is closest to cash flow when investments roughly correspond to depreciation.

Of course, it should always be remembered that the EBIT of a given year often does not represent the “true” company result. Therefore, EBIT is normalized, meaning extraordinary income and expenses or special influences from shareholders (e.g., salaries, vehicles, rent) are excluded from the income statement.

In addition, the reference year has a significant influence on the value. Typically, the current fiscal year is used (current forecast). Using only one year may not adequately account for growth potential or cyclical trends. Therefore, adjustments may be necessary to achieve an appropriate basis.

If the potential is sufficiently specific, it can be adjusted. Under certain circumstances, average values from several years can be used, taking into account both the planning and the past. In the current COVID-19 crisis, this allows companies to be appropriately valued.

Comparable Transaction Analysis

The first method is based on comparable transactions (also called comparable transactions). To form the comparison group, transactions involving companies from the same industry are considered. This method is based on the idea that multiples paid in the past for transactions already completed also reflect the “fair market price today.”

The valuation approach based on transactions of comparable companies has significant strengths when it comes to valuing companies that are not listed on a stock exchange and are usually much smaller, more focused, and more regionally positioned than their generally much larger, more broadly diversified, and more international listed competitors.

Unfortunately, however, the valuation process also presents difficulties in practice:

- The available information is often insufficient, as details of transactions involving private companies are often not published or are not published in full.

- The period from which the transactions originate must be very long in order to obtain a representative base set of data. Since the valuation of industries changes over time (e.g., due to changes in interest rates, technologies, or growth prospects), the values determined in this way may differ from the current value.

Comparable Listed Companies

The second method is based on the valuation of comparable listed companies (also called trading multiples or trading comparables). The idea behind this method is similar to that of valuation based on transactions of comparable companies:

The consultant creates a peer group of listed companies that are as similar as possible to the company being valued. With this method, the multiple is determined as a multiple of the market value of the financial ratios (EBITDA or EBIT) of the listed comparable companies.

This method offers the advantage that the data for listed companies is current, fully publicly available, and relatively easy to collect.

The disadvantage is that publicly listed companies are often very limited in their comparability with non-listed German SMEs. Imagine comparing Coca-Cola with a medium-sized, regional beverage manufacturer in Germany. Don’t the dissimilarities outweigh the similarities? Compared to publicly listed companies, SMEs are often more regional, smaller, and more focused. Furthermore, shares in publicly listed companies are highly fungible, meaning they can be sold at any time in variable quantities without time expenditure and with minimal transaction costs.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Method

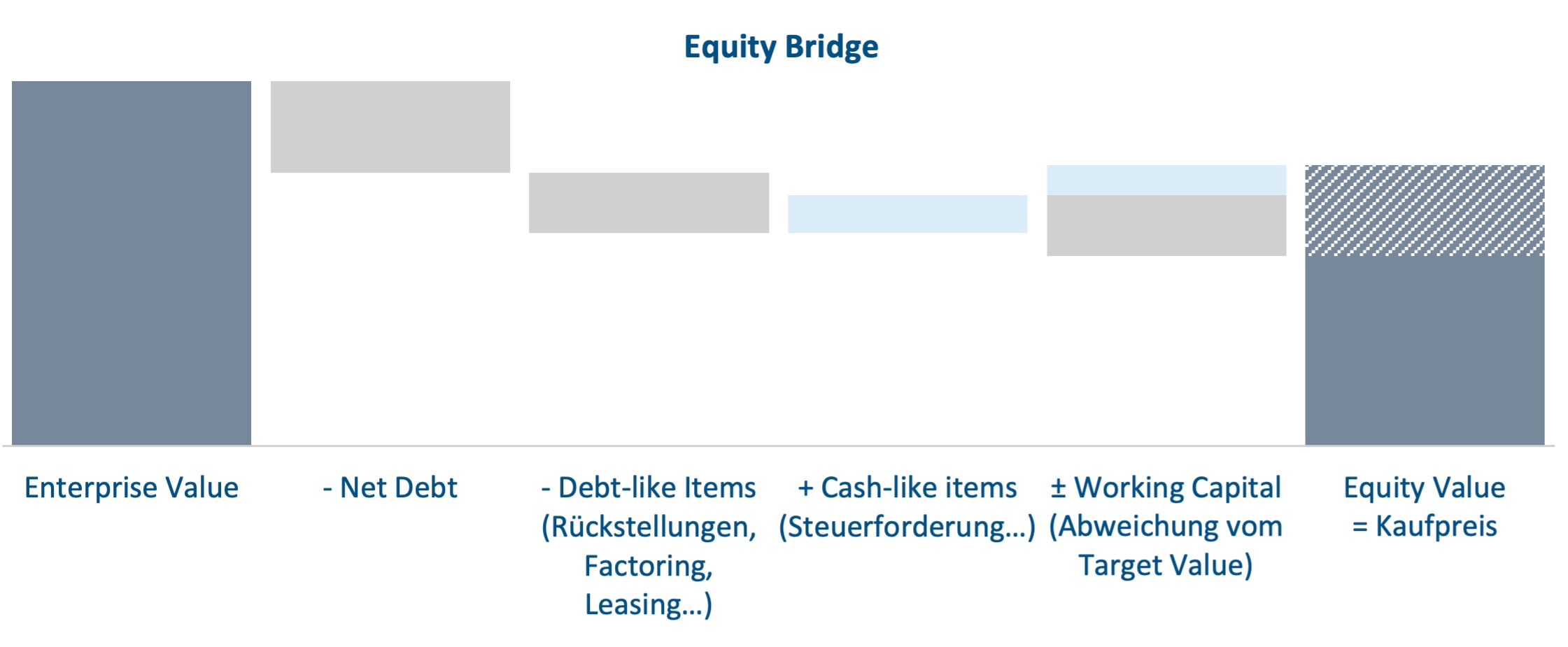

To calculate the company’s value using the discounted cash flow (DCF) method, the company’s future cash flows are forecast and discounted using a risk-appropriate cost of capital. With the DCF method, the company’s value is essentially determined by the assumed sustainable cash flow at the end of the detailed forecast period (“perpetual annuity”). The present value of this perpetual annuity can amount to 60-70% of the company’s value. In contrast to the discounted cash flow method, the income approach focuses not on cash surpluses, but on earnings or net income. In a typical M&A process, the income approach plays a negligible role. In the discounted cash flow (DCF) method, gross approaches dominate in the M&A environment, in which the cash flows to equity and debt providers (so-called free cash flows) are discounted using the weighted average cost of capital (weighted average cost of debt and equity, or WACC). The purchase price accruing to equity providers is then determined from the company value thus determined by deducting net financial debt.

The strength of this method lies in its accuracy, as it fully maps a company’s future development, including future investments and the development of working capital. This is why this method is also the method favored in valuation theory.

In practice, however, this method often encounters difficulties. Firstly, the cost of capital is derived from comparable listed companies. These are only transferable to medium-sized companies to a very limited extent for the reasons already mentioned above, such as size, diversification, fungibility, etc. Secondly, the planning period of 3-5 years involves planning effort and corresponding uncertainty.

Net Asset Value Method and Non-Operating Assets

The company valuation methods mentioned so far assume that all assets transferred with the company are necessary to achieve the planned EBIT results. This naturally also includes inventories within the usual range of coverage. The value of these assets is therefore included in the company value and does not need to be considered separately. Therefore, the net asset value method is generally not used in company valuations.

However, the situation is different when there are non-core assets: The value of these assets can be realized in addition to the company value.

When selling a company with significant real estate assets, the net asset value of these properties may also be relevant in some circumstances. If the net asset value of the real estate assets is high, it may be advisable in the event of a transaction to separate them out beforehand and then sell them separately or rent them to the new company owner.

Liquidation Value Method in Company Valuation

The liquidation value is calculated from the value of the individual assets less the liquidation costs.

The liquidation value method is only used to determine the company value if the values of the multiples or DCF methods are below the liquidation value. In concrete terms, this means that it appears more profitable to sell the company’s assets than to continue the business.