What do I need to know about this?

The following issues typically apply to transactions with companies in the software industry:

Capitalization of Development Costs

Companies in the software industry typically incur significant upfront research and development costs for the development and further development of their products. Under German commercial law, there is an option to capitalize these costs (Section 248 (2) HGB). If this option is exercised, the costs are neutralized in the income statement and an asset is created on the balance sheet and depreciated over the useful life. Capitalizable costs include all internal and external development costs (i.e., personnel, materials, consulting, etc.). Research costs, on the other hand, are explicitly prohibited from capitalizing.

If the valuation is based on an EBITDA multiple, the company would increase its EBITDA and thus its valuation by making maximum use of the option, as expenses above EBITDA would be eliminated and depreciation of capitalized fixed assets would be incurred below EBITDA.

Classic arguments for or against adjusting EBITDA based on capitalized development costs typically include the following:

- Since capitalization is not “cash-effective” and development costs are actually paid, buyers often argue against eliminating them from EBITDA.

- On the other hand, there is the argument that the “peer group,” on which the EBITDA multiplier is often derived, is also subject to the capitalization option, thus comparing “like with like.”

- According to international accounting standards, capitalization is also mandatory (IFRS, IAS 38), which represents an additional argument for sellers, compared to a buyer preparing financial statements under IFRS, for full elimination from EBITDA.

Shareholder Costs

Companies for which a sale occurs, e.g., as part of a company succession, are typically owner-managed. It is not uncommon for shareholders to compensate themselves either through their salaries or consulting contracts. Depending on the proposed post-sale structure, the current shareholders, i.e., the current management, are typically replaced by new individuals with market-standard salaries.

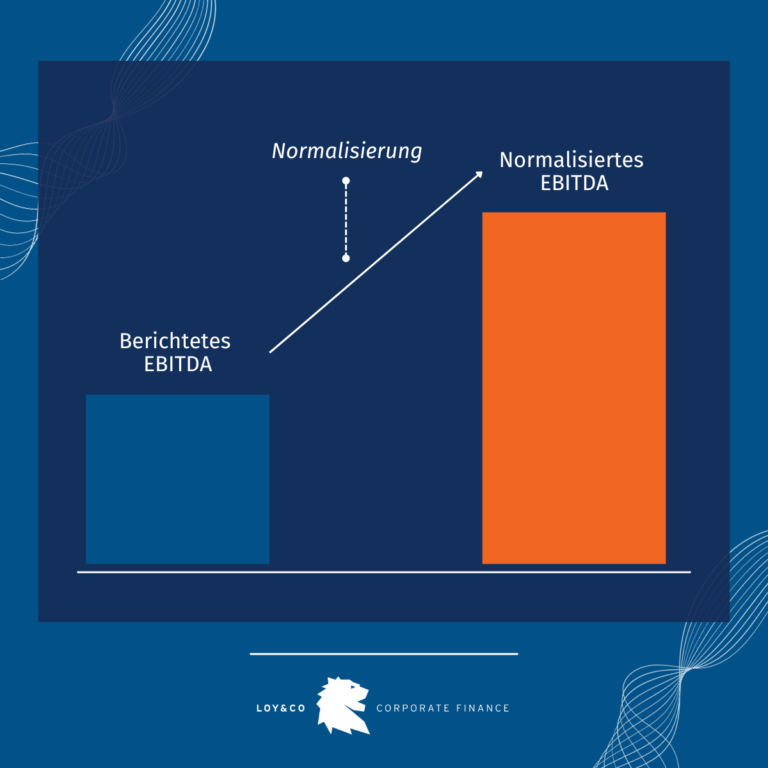

For example, if a shareholder paid themselves €200,000 per year in the current structure, but an acquirer can hire a managing director for €150,000 in the future, the result would have to be “normalized” or increased by the difference of €50,000. If the acquirer is a strategic buyer who can replace the management function with existing functions within its organization, the total amount could possibly even be normalized as a synergy.

In addition, the company often has ties to the shareholder or their families (e.g., employed family members, privately used company cars, etc.). These often relate to costs that would not be incurred after a sale, or would not be incurred to the same extent, and therefore represent potential for normalization.

Classic arguments for or against shareholder-related issues typically include the following:

- The adjustment of shareholder compensation and shareholder-induced costs is generally accepted by most market participants, while the exact amount of normalization is at most subject to negotiation.

- In the case of synergies with a strategic buyer, buyers frequently argue that they do not want to (fully) incorporate the synergies they have generated into the purchase price.

One-off income and expenses

One-time income and expenses are regularly normalized from EBITDA if they either

(a) do not arise from the original operating business model or

(b) are not recurring in nature.

Since both aspects can rarely be clearly defined, these normalizations lead in practice to significant discrepancies in purchase price negotiations.

A common point of discussion in this regard is consulting expenses. Companies often have a large number of consulting projects, which, individually, are often unique in nature (e.g., marketing campaigns, transformation projects, etc.). However, if these total similar amounts over a longer period, this could indicate that consulting expenses of this amount are indeed normal and sustainable for the company.

Other typical one-off items include:

- Gains and losses on the disposal of property, plant and equipment

- Costs related to legal disputes

- Extraordinary bonuses, severance payments, or recruitment costs

- Currency gains and losses

- Exogenous circumstances: e.g., COVID-19 aid, temporary closures

- Any costs in the operating result with a financing character

Out-of-period income and expenses as well as provisions

Out-of-period expenses are costs that arise at a later date due to operational circumstances (e.g., an advance payment) and therefore cannot be allocated to the current accounting period. Income from other periods is the corresponding counterpart on the income side. As part of the due diligence process, these income and expenses are typically retroactively allocated to the correct periods. In terms of amount, these amounts are usually insignificant.

Since the adjustment is also of a technical nature, there is rarely a need for negotiation. The same applies to the reversal of provisions. Here, the reversals and the respective additions to the previous period are normalized to the same amount, resulting in only a periodic offset.